Welcome to the Chockalife podcast. My guest today is Scott Einziger, an Emmy-award winning producer of groundbreaking reality shows like The Howard Stern Show, The Amazing Race, and Big Brother. Now, he sets his sights on independent film forming his own production company, Unguarded Content and developing stories into film, scripted, and reality television; based on real people and real stories.

Welcome to the Chockalife podcast. My guest today is Scott Einziger, an Emmy-award winning producer of groundbreaking reality shows like The Howard Stern Show, The Amazing Race, and Big Brother. Now, he sets his sights on independent film forming his own production company, Unguarded Content and developing stories into film, scripted, and reality television; based on real people and real stories.

Welcome, Scott. Thank you for joining us today and talking about working in Hollywood and being a producer.

Scott: Thank you for having me.

Sure. Can you tell me a little bit about what you’re working on right now?

Scott: Right now, I am trying to make independent movies and self-funded my own production company with a partner, and hustling it out every single day.

Did you start out making independent films? Tell me about how you got started in the business.

Scott: I went to film school and graduated from Ithaca College back in 1988, and knew that Hollywood was sort of the Promised Land. Meaning, if you wanted to work in the business, Hollywood is essentially where all the decision makers live. With bright eyes and a buddy, my college roommate, we got in a car, drove out to Los Angeles not knowing a soul – with a resume in hand, but very single-mindedly focused on getting a job in film.

Did you always know you wanted to go to film school? How did even film school start for you?

Scott: I suppose I was fortunate in terms of career goals since I was eight years old. I was the kid who was making Super 8 movies in the basement, and showing, you know, worked on the AV squad, and that kind of thing. I was always involved in some form of media, be that at my high school, a local cable television show. My passion was to work in films even despite having some fortunate experience working for a commercial TV director as an internship during college. A long way of saying, I knew what I wanted to do since I was little kid.

When you drove out to LA, I mean, that’s just like the quintessential story. Did you have a list of people to get in contact with or what did you think would happen?

Scott: No, I had nobody. There was no one. All I had was a resume which consisted of my internships that I did during college. I was willing to do anything which at that time, you know, the two go-to places were to buy every morning at 7-Eleven the Daily Variety and The Hollywood Reporter which had a classified section.

Right. (laughs)

Scott: No joke. You don’t read them that way anymore. I mean, publishing has changed. I would look at the classifieds, and I guess my story is sort of typical and that the only job that I could get, and the only job that I ended up getting was an assistant … this is back in 1998, as an assistant at a very small talent agency making $120 a week. That was my first job in Hollywood.

Probably working 80 hours or something ridiculous.

Scott: It was long, and I knew after a while that my heart wasn’t into wanting to be an agent. I felt like, and not in an arrogant way that my dream was actually to be a client of an agency one day. I left after a year and went back to looking at the trades and the newspapers. This is a pretty classic story. I ended up getting a job at a video store which at least to me, at that time, had a benefit which was … They don’t really have video stores anymore. This one was actually a pretty cool one in Westwood which had a really good selection of films and genres, and a lot of celebrities would come in, directors. It was basically a Mom and Pop Video Store. One of the benefits of working there was that you were able to take home movies for free. That was a cool benefit.

This is starting to sound a little bit like Quentin Tarantino.

Scott: It’s pretty much the same. It’s pretty much the same, and would love to have his career, of course. Yeah, I mean, he did the same thing. He worked in a video store. While I was working at the video store, I knew that that wasn’t going to be my dream come true, and continued to look into the trades and saw an ad for a job which was titled Tape Library Assistant, three to midnight shift at a cable network called Movietime.

I looked at it and I said, “Well, I have the perfect credentials. I’m working in a video store. I’m totally, totally trained up to be an entry level video tape librarian at a cable network,” and that was in June of 1990. I got the job. It didn’t pay enough so I actually worked both jobs. I worked five days a week, three to midnight at Movietime which was essentially a startup cable network that promoted entertainment news. They aired some of the interviews, behind the scenes material, that sort of thing. I serviced the producers at the network who had to cut pieces. I didn’t make enough money so I still worked at the video store on the weekends.

In terms of the stories of how, you know, whatever it takes, I mean, I did whatever it took and for me that was working both jobs. Then something fortunate happened which I was unaware of, and back in June of 1990, when I took the job, what I did not know is behind the scenes, HBO and Time Warner had plans to buy the fledgling network and turn it into E! Entertainment Television. In June of 1990, I was there for the launch of the cable network which was very exciting and very rare. It doesn’t happen that often.

From there, I decided, well, I wasn’t going to want to be a tape librarian for my career but the benefit of working at a cable network and working in the tape library is that I interfaced with producers in every single department. That would mean, I interfaced with producers from the news department. I interfaced with producers from live events. I interfaced with producers from more long form programming, the on-air promotion department.

Since I was working the three to midnight shift, there was some slow time so there were some kind producers who’d allowed me to sit in their edit bays and explore what they did. I had sort of a bird’s eye view of what the different types of producers are within a cable network and the different departments. By the way, there was also the marketing department, many departments that make up a cable network. I’ve decided that having gone to film school, that my choice if I had it was to work for the on-air promotions department, and that’s the department that creates the 30-second promos, little commercials, right, that promote the programming.

The reason why I made that decision is that I saw that the on-air promotion producers got to work with the best editors because there was also graphics involved. They got to sometimes actually direct shoots. They got to direct voiceover talent. The best part of all is every time they produce a 30-second spot, you could aggregate a reel, like real examples of your work. I figured that that was the department that I wanted to end up in, and I begged and begged and begged, and plead with all the producers in the on-air promotion department and the head of the department that the second a production assistant job opens up on on-air promotion, can I please, please, please have the job? There was a lot of begging involved. That happened for me.

Once I became a producer at a cable network which was, you know, if you look at E! Entertainment Television today, it’s a huge company. I’m guessing, maybe with 2,000 employees and owned by Comcast and a part of a big, super structure. Back then, E! in 1990 when it launched, it was 200 basically kids in their 20s. There was a lot of opportunity. As a production assistant, I was able to actually produce and go in the bay and finish a spot, and walk into the head of programmings office with my boss, and show them the spot, and see it air 50 times a day. It worked for me.

It’s almost like you’re getting a crash course in real life filmmaking because those 30-second spots actually have to tell a story, and they have all the different elements that you might have in something more long form, and you have to kind of make it interesting.

Scott: Yeah, it’s a good point. What it taught me … It’s actually not to say, I mean, it’s all hard but to tell a story in 30 seconds is sometimes more challenging than telling a story in 22 minutes, right? It forced me to use my writing skills because I was responsible for writing it. I was responsible for working with the graphics department. I was responsible to sit with an editor. Back then, Avids didn’t exist. Non-linear editing did not exist. You had one edit session. You had to have screened your tapes back then – for any of you who are in their 40s, you know, three-quarter inch or 1 inch reels. You got to have your paper cut, and you have one session to essentially get it right.

It was a good learning experience for me. I also like the sort of … au tour element of it because it was my single vision. If the script got approved and I would sit with an editor, I basically lived in an edit bay as I progressed up the food chain in on-air promotion. I started as PA, got promoted to an associate producer, got promoted to a producer, got promoted to a senior producer, and then I think I got promoted to a supervising producer. That’s how I sort of earned my producer’s stripes within that department.

It also kind of tells a story that no matter where you start, it’s good to be in a smaller arena so that you can do all kinds of things and that you’re allowed to do other things. Rather than, if you work for something gigantic, you’re really going to be pigeonholed. Sometimes, these really small arenas are good to get all that experience.

Scott: Yeah, I agree and the benefit was I also got a lot of attention which meant to say that when the spot was done, it had to get approved by either the head of programming, sometimes I got marched into the president’s office at that time, a gentleman named Lee Masters. You were patted on the back if they liked it. If they had notes and didn’t like it, you were sent back to the bay but it was certainly good in terms of having to use a lot of different skill sets but also getting exposure. Then, like I said, building a reel. Every time I finish a spot, I edit it to my reel and it became something that I knew that could be portable if in the event I want to get another job, but that’s not what happened actually. There’s a little bit of twist in my story in terms of the next phase in my career.

Well, yeah that’s what … Because most people, once you get into that studio job or you work for Discovery or any of these big networks, it’s really difficult to make the leap out into anything independent after that. How did you move on from there?

Scott: What happened was and this is more of a personal decision, but I was young and I was at that time dating someone in New York, and I made the decision at probably, oh my God, 23-24 years old that I was going to quit my job at E! and for love, moved to New York to be with this woman. Everyone at E! told me I was out of my mind, you’re too young, and you’re on to such a great trajectory. I’m pretty strong willed and I live my own life. I told them that, “I appreciate it. You guys have been great but this is my decision. I’m going to New York.”

There were some conversations behind the scenes that I was unaware of and I’m grateful for it. E! Entertainment Television actually created a job for me in New York. I was the first producer for the company in New York fulltime as they were growing and having to expand their breath of entertainment coverage. Literally, I didn’t leave the company but I moved to New York and had a desk in the ad sales department. Whenever they needed a celebrity interview or someone to cover a press junket, they just called me. That was my existence at E! for a bit.

Then, something else happened which sort of formed, I think the balance of my career, and it’s the following. E! had entered into television deal with Howard Stern, the famed radio show host who’s also now, for your younger listeners a host on America’s Got Talent. Having grown up in New York, I was a huge Howard fan. They had talked about doing a stripped, nightly television series where they would put robotic cameras in his radio studio, and since Howard for some people was considered or still is considered one of the best celebrity interviewers, that we would record the radio show.

Since I was in New York, it made sense to pair me with Howard. In June of 1994, I was with a very, very, very small crew and not a lot of resources, and no one had really done this before, no one had really taken a radio show and figured out how to make it telegenic. By nature and design, radio shows are static. I was young. I was 25 at that time, and working with Howard who’s amazing, and smart, and brilliant but also it’s Howard Stern. Howard was also on radio at that time, and reaching 18 million households, and he was a big deal but he also came with another staff. It wasn’t just sort of one talent to do it. It was a handful of talent. I set off to figure out how to turn his radio show into a TV show.

That was for E!?

Scott: That was for E!. It was just called Howard Stern. It aired every night, I think at 11:00. What I did which caused a lot of fury back at the home office in Los Angeles is, since I was a fan, and I’m not going to take full credit, but I think you know, at that time, Howard and I, you know, we’re sort of both on the same page because I understood the show. As a fan, I decided that the celebrity interviews were fine and I understood their value to E! but I felt that the late night audience also wanted to see some of the wilder things that they heard on the air but didn’t believe, like “Is that really happening?”

Also, and this is where I think I was lucky to be a part of one of the first sort of workplace docu-soaps is that there was always a lot of conflict amongst the staff, and it was sort of part of the fabric and DNA of Howard’s show. I started programming episodes that were wild and racy. For anyone who’s seen the show, there was a lot of blurs. Then, I also started programming fights, fights between the staff and put cameras behind the scenes, and the E! corporate folks back home totally freaked out and said, “That’s not why we did a deal with Howard.” But the proof was in the ratings.

Yeah, it was a hit. That’s what people wanted to see.

Scott: It was a hit. Just to give some context, at that time, E! was a 0.2 network in terms of ratings. That’s fine. They were a young network. We were doing sometimes a 1 or over a 1 rating which was huge. Once the ratings came in, they left me alone. I ended up staying with Howard for actually a decade, almost 10 years.

Along the way, would you say that there were a few people that helped you particularly or would you say it was just kind of happenstance, you know, working really hard? What would you say compelled you?

Scott: To name names, I mean, I had a very supportive boss in a gentleman named John Rieber. I mean, I had the support of Fran Shea at that time who was the head of programming. I had the support of Lee Masters. My biggest supporter and my leverage was Howard. Once Howard trusted me, E! kind of left me alone and I had a staff in New York, and I kind of ran my own ship.

Howard, because he was a big, important talent to the network and it was the highest rated show at that time, and having a relationship with him and learning a lot from each other, you know, he’s a broadcaster. I think that he had a lot to do with my ability to function and execute, I think what he’d be proud of and what was my vision. Then, I also had an amazing, tireless crew and had to integrate with the radio staff as well who were very supportive.

That’s kind of an important point, too. I mean, it helps if you can get in with a talent and they support you because then you can have free reign especially if they’re as big as someone like Howard Stern. It really gives you a lot of leverage.

Scott: You know what? I was young and full of … I don’t know if you can curse on your radio show but I was full of piss and vinegar. I was smart. I did leverage of Howard, and if there was something that I knew he wanted or something that he would want, I wasn’t afraid to say, “Okay. Well, you can tell Howard no if you’d like,” because he is a big force and not that I had any evil intentions but I cared about the show because a lot of the things that he did and a lot of the things that we aired were controversial.

There was plenty of conversations with Standards and Practices, and there was a lot of battles to be fought. There were times when we had to do shoots that were outside the scope of just the cameras in the studio. We did two giant event shows each year that were 10-camera shoots. We would do hidden camera shows. We would build game show sets. We had bands. You know, sometimes it required asking E! for more money. I mirror your point is that if you do have someone who’s sort of higher than you in the food chain, that is your partner in this, you can sort of use that and I did. I mean, I did.

I think it’s all about timing, too – to sort of know when you have that power and use it wisely, and recognize it because you can miss a lot of opportunities if you just sit back and wait as well. You have to really … You’ve to be proactive about everything and looking out …

Scott: Yeah, I agree. I mean, you want to pick your spot. If you overuse it, then you become a bully. I think, as a young producer, and again, I was in my mid-20s as the executive producer and show runner, for the highest rated show on E!, you know, I felt a lot of weight on my shoulders. You know, whatever I could do to get the job done, I did and also to please Howard. He had high expectations. Also, you become part of the radio show story. I would get pulled on the air often, usually to get yelled at. Sometimes you hope it’s not to get yelled at. I really was there, for anyone who’s a fan, I was really there for probably the best 10 years in terms of just significant things that happened in the show.

Yeah, I remember that time. That was a new way to do things. That was a bit of a groundbreaker there, that show.

Scott: Yeah, and the shows followed. You could see, you know, there were shows that started to follow that paradigm. Most of them being actually more news oriented or sports talk shows. You can see a lot of shows on the air that have sets in their radio studios and I think Fox sort of followed what we did. It was a trailblazing experience that I’m grateful that I had, and to everyone at E!, and to Howard and my staff.

However, after 10 years … You weren’t allowed to complain about much working for Howard but there was one thing you could complain about, and that was the hours. Howard would go on the air live every morning at 6am which meant most of us had to get up before, you know, around 5am and be at work ready to go at 6am in the morning. Although the radio show ended at noon, I still had to produce a radio show. At that time, in the beginning, I didn’t have a big staff. I would leave the radio show. I would run with the tapes and switched a line cut which was sort of the director’s vision of the show, and then we had two ISOs, which should be two isolated cameras. I would run to National Video in New York, and I would have a deadline. I’d have to make the satellite feed at 7:00.

It was very challenging at that time. Sometimes, it was like the movie Broadcast News where you’re running down the hallway trying to get the tape in. Overtime, Howard was instrumental in realizing that he had to kind of serve two masters, and one was that he would have to do a radio show and sometimes doing a radio show is just him talking or talking about topics – which was not telegenic. Then, he realized that he had to serve the TV side and give us content that was visual.

Some days, we would … we called it the bank. We would bank more material than we needed just to fill out five nights a week. We had a surplus of material which then alleviated me having to … have a nervous breakdown every day by trying to make a delivery. We would bank shows which took the pressure off, and then the beauty of it was if something amazing happened that day in the studio, that the audience was dying to see, we still have the ability then to turn our show around and air it that night if we needed to. We kind of have the best of both worlds.

Boy, that sounds like a grueling schedule to do for 10 years.

Scott: Yeah, it was rough and after 10 years for me, you know, I felt like the notion of being back in California and Hollywood was sort of beckening again. Primarily what happened was that around 2001, early 2002 I started to see that reality television was becoming a primetime business which is to say that the networks were giving up primetime slots to shows like Survivor 1, Amazing Race 1, Big Brother 1, Bachelor 1, American Idol Season 1.

My gut told me … and it was hard to leave Howard. He was very loyal to me and I certainly was loyal to him. I felt like I had done my job and set up the system, and there were those below me that I thought it was time for them to step up, you know, sort of passing the baton. I said to my agent at that time, I want to get into that. That meaning, I’m pointing as I talk, that meaning primetime television. Sorry, primetime reality television. That was my plan.

I knew Howard wouldn’t be thrilled with my leaving but I was at the point where I guess, honestly I wanted to sort of make my own way, and I saw an opportunity and a window. I knew that that window would close in terms of again, first responders to a new business model. I was in California, because E! was based in California. I would make trips from time to time, and my agent … I was literally supposed to fly black to New York the next day, my agent said, “You need to go and take a meeting with a gentleman name Ghen Maynard who is the head of alternative at CBS.

Ghen was the one who discovered Survivor, discovered Amazing Race, launched Big Brother. He’s a super, super, super smart guy. Said, “You’re going to go meet with Ghen that The Amazing Race is looking to do a restructuring for their second cycle, and they’re looking to bring in some new meat, fresh blood. They’re looking for someone to come in at a co-executive producer level; one person to oversee frontline logistics and one person to take over story and post- production.”

After meeting with CBS and then being promptly sent over to meet with Bertram van Munster who created The Amazing Race with his wife, Elise and was the executive producer, I was quickly dispatched after meeting with Ghen at CBS to meet with Bertram. My funny Bertram story and it may not be relevant to people but if you know Bertram, this one will count. I was a huge fan of Cops. Many people may or may not know this but Bertram was the original cameraman for Cops. Bertram had sort of been the guy in the Cop car who developed that technique of shooting.

To me, there weren’t many sort of reality rock stars in reality TV but I was enthralled to meet with Bertram. There was definitely a lot of sort of acknowledgement of Bertram and …

That was groundbreaking. Cops was groundbreaking. I worked at Fox Studios when that was out. I mean, people had never seen anything like it. It was amazing.

Scott: That was him. I’m sitting there meeting with somebody who was in an odd way, sort of an idol of mine because he had worked in that show and I think he had worked his way up to the ranks, and obviously left it. I definitely kissed the ring but totally from a genuine place which I think worked. I was given another phone call … this is all happening within the same day. I was called back by my agency who said that CBS and Bertram would like you to stay in Los Angeles for a month and see if you could sort of help them in the edit bay.

I’m like, “I have a job. I’m responsible for running Howard’s show.” My agent at that time, his response was, you know, this is about your future. I don’t specifically remember how I convinced my boss at E! or Howard that I was going to stay in Los Angeles but I do recall that I was pretty transparent about my desire to move to Los Angeles. I don’t think it was a huge surprise. I literally moved into the Oakwood Apartments in Marina Del Ray, and lived in an edit bay for a month, I think.

My assignment was to cut episode 12 season 1 of The Amazing Race. That was my test. Based upon the quality of the first cut, meaning how many notes I was going to get from CBS and Ghen would determine if I would get the job. I got the job. It was bittersweet leaving Howard but I ended up on a big production, you know, Jerry Bruckheimer’s name attached and I was in it.

I was in the primetime reality game. I thank him all the time, and I do tell Ghen Maynard that if I think of one person who really gave me my big break and took a chance on a guy who had worked on a show that wasn’t … There were no really other shows to point to like Race but he definitely took a chance on me, and he was definitely somebody who I’m forever grateful in giving me a big break.

It is interesting – just your story – because it does happen like that. Things can just kind of almost come out of the blue and suddenly, you’re taking a major 90-degree turn on your career.

Scott: Yeah. I’ll accelerate the story a little bit. They hired someone else to be responsible for the other half of the show, all working in conjunction with Bertram. I worked a year straight. We did Amazing Race 2 and got through 13 episodes, and worked on Amazing Race 3 and I pretty much worked a year straight probably without a day off. There were times where I was actually sent home. Bertram would send me home, “You look green and you look like you’re going to die, so we’re going to send you home.”

I wonder if it’s still true. The Amazing Race is the hardest reality show to do.

Scott: Yes, hands down.

I don’t think anything’s beat it. It’s just 24/7 or however long you work on it and intense.

Scott: The difference for me was that if you worked on the production side and the logistical side, you had a little bit of a breather between seasons. I didn’t, because not only was I working on the show that was being shot, I was then having to edit the episodes which then led into the next season. I didn’t really catch a break. After setting up the system which is still the same system that they have today, in terms of the editing scenario and sort of getting it right, I have made the decision that I felt like, mission accomplished. I did my job. Although there’s many, many fine people who are still on that show, I chose to leave and it was all amicable and with all good wishes.

I ended up getting hired by Mike Fleiss who had created The Bachelor, who has sold the show to ABC’s Are You Hot? The Search for America’s Sexiest People. Mike was under an overall deal at that time with Telepictures, which is now Warner Horizon, in terms of primetime programming- but I got hired to show run, Are You Hot? The Search for America’s Sexiest People – and that was another test. When I passed that test, I was offered an overall deal at Warner Brothers to show run shows for Mike that were not The Bachelor. I had sort of graduated to a bigger league as a full-fledged show runner and did a lot of shows for ABC.

At that time, we had a first look deal with ABC. I think we had a second look deal with CBS. I did a show at that time for The WB.

When you say show runner, what exactly are you talking about?

Scott: If one were to watch the credits on a reality show and actually a scripted television show, there may be many executive producers but there’s typically one show runner. That’s really the person who I’d say is the day-to-day general in charge of getting that show done from casting to preproduction, to execution in the field, and to editing. The best way to explain it is as the show runner, if the network’s happy, you get the phone call. If the network’s pissed, you get the phone call. You’re really the guy in charge and leading the troops every day to accomplish what has to get done.

When you talk about first look deals, what does that mean?

Scott: There’s a lot of different deal structures in Hollywood but the first look deal meant that at that time, Mike Fleiss’ production company, anything that Mike came up with or created or anyone on his team would have to get pitched to ABC first. They had first rights to the show idea. Back then, Bachelor was the highest rated show on ABC. Mike had a lot of sway, and they would typically buy anything that came out of Mike’s mouth which doesn’t happen much anymore by the way. It’s very rare to go in, pitch a couple of sentences, and then walk out and say, “Would you like it or not?”

We were in a unique position. I think at our maximum, we had seven network shows on the air. That meant that ABC had the first rights to the show, and typically they snatch it up. If they pass on the show, and they don’t know the particulars of the deal, Mike Fleiss probably had the right to shop it to another network, or there were some kind of holding period. Essentially, a first look deal is where a buyer has a relationship with the seller or a content producer, and they have first dibs at your vision and your ideas.

If ABC bought it, then he would assign different show runners like you to take over the show.

Scott: Essentially, yeah. At that time, there was a show runner, a very talented show runner named Lisa Levinson who was in charge of The Bachelor, and then there was me who was typically assigned the non-Bachelor shows. Then, there was another level of producers who you would sometimes get paired with, very talented producers and producers have gone on to do great things, but yes. Mike would sell the show. You’d get assigned a show or I would get assigned my show, and then it’s when the hard work begins because when the show was sold in the room, it was a high concept pitch. It was maybe a 15-minute meeting.

Once it was bought and the deal was negotiated between the studio and the network, I would then have to basically, what I call break the format, and essentially figure out how to do the show. Not only do the show but do it within the confines of the budget. The budget’s four-walls, and it is what it is and I was always told what my budget was. My job, once I was sort of given the reigns would go back to the network and then we’d re-pitch the show in a much more substantive and granular way which is – here’s how the show works, and we walk them through the show.

Once they signed off on that is when you would start hiring department heads, usually casting first, some producers, and then start building your staff, and off you go.

You spent quite a while doing some pretty high-level reality shows, and now you’ve transitioned into a different format. How did that happen?

Scott: I did. I had a blessed career with Howard. Actually, season 3 of The Amazing Race won their first primetime Emmy in the competition category. I won the first Emmy for Race. I think it’s since won nine, but I’m certainly proud to have won the first one. Then, having a very productive experience at Warner Brothers. After I left Mike at Warner Brothers after five years, I did an overall deal with CBS and I did a couple of big shows for them.

Truthfully, I was burnt. I mean, it happens. I had been working, at that point almost 20 years straight and decided that I was going to try to do something different but not take a turn that was so widely entrepreneurial that it didn’t rely upon my skill sets. My decision in going back to the kid who was working in the video store and back to the kid who couldn’t get a job in the movie business, I decided that I wanted to make movies. The way I did is I kind of bought my way in, and I can give some context to that.

But I was represented or still represented by Paradigm, the talent agency and I had read an article that inspired me and moved me that I felt had the makings of being a movie. I reached out to the agency and I said, “I think this is a movie but I’m not quite sure how this all works. I’d like to be a movie producer.” Sort of like, naively asked them that question having been a reality producer. They knew I had a story. They knew I had a story that I was pursuing the life rights for. They basically said, “Can you write a check?” I’m like, “What do you mean, can I write a check?” “Well, can you write a check to hire a legitimate produced WGA screenwriter?” And I said, “I think I can write a check.” They said, “Then, you’re a movie producer.”

Literally, that would start it. I met with some of their writers and ended up hiring an amazing writer named Ryan Jaffe who had sold a lot of projects, and he’s had a movie produced and had written some scripts that were new and notable around town. He set off to write this movie for me called Referee which is based on one of the youngest referees in the NBA who fulfilled his dream. At the age of 16, this kid decided that he wanted to be an NBA ref. There’s only 60 spots and he made it. It’s kind of an American dream. It’s a little bit of a comedy as well. It’s based on a true story, and I think it’s a very inspiring story.

It sounds a little bit like a Hoosier’s kind of thing.

Scott: It’s that. It’s definitely got, like Bend it Like Beckham. It’s got a little bit of Billy Elliot, you know, and maybe dosing a little bit of Rocky Story II. It also has a culture element. His family had emigrated … This particular referee, his family emigrated from Ukraine and they were homeless in Manhattan. That Russian culture, you’re parents wants you to assimilate. They want you to become a doctor, a lawyer, or an accountant. This kid wanted to be an NBA ref.

He was surrounded by a bit of dream killers which I think touched me because I know a lot of colleagues and friends that I speak to in the entertainment business have parents which are from a different generation who don’t understand … I don’t even think my parents even still know what I do, you know, after doing this for 20 years. But this story spoke to me and from that experience, and not really knowing the independent film world, Ryan, the screenwriter approached me and he had been thinking about transitioning into a producer.

All sort of like, the planets come into alignment, me wanting to transition from being a reality show runner to a movie producer, Ryan being a screenwriter wanting to transition into a movie producer. We had many, many conversations about forming a production company, and we did. That was about a year-and-a-half ago since that conversation.

How were you finding it different from the reality world? Because it’s vastly different.

Scott: It’s equally exciting and equally horrifying. It’s very, very hard particularly in the independent world. The reason why it’s called independent filmmaking is that the traditional system, the big studios, even the agencies to a large extent, they don’t look at the independent world as a real moneymaker for them. Although you can point to many independent films that have made a lot of money, it doesn’t really fit into the system. You’re sort of working outside the system and the hardest piece of it.

The reason why some movies get made and some movies don’t is that not only are you financing and developing the material which is money out of your pocket, you’re trying to raise the money for the budget. It’s very, very hard to raise money. It’s a risky investment for most and it’s needles and haystacks. We hustle every day, and we’ve had some success in raising portions of the money for some of our movies. We now have three movies, three movie projects that we’re raising money for but there’s also the element of packaging which is chicken and the egg.

While you’re trying to raise money, you’re getting your script out to talent via casting director and you’re trying to attach talent which would therefore entice perhaps the investors. It’s all very sort of an interesting dance. Does that make sense?

Yeah. From what I’ve seen and the people I’ve worked with, basically if you can get some talent attached and someone who has, who people will go and see, that really seems to be the key for every independent film to get financing.

Scott: The trick is that the ones that … The talent that means something, you know, have a hundred projects in front of them. What you hope for is that someone falls in love with your script, and a lot of celebrities or a lot of talent bounce between doing big Hollywood movies, right?

Right.

Scott: And bounce back to doing independent films because they both offer two things. One I think offers a big paycheck, and God bless them and profile and one offers, you know, sort of art and more creative freedom, and not working under the system. It’s like how do you catch that actor who’s maybe coming off of the big movie and wants to do a small movie? How do you catch them in your net? There’s a lot of rejection but you have to have a lot of fortitude and tenacity which we do, and I mean, it’s a hustle. We hustle every day. We think of ways to crack open potential financing. We think of ways to get to talent, maybe not necessarily through the normal channels. You have to be really out of the box.

Right. That’s when you become really creative. That’s the most creative stories or people with scripts that are trying to get to talent because they’ve got all those gatekeepers that are specifically trying to keep you from doing that.

Scott: One side of me respects the system, and I understand the system. I’m part of the system. I use an agent from my reality business, and we have agents who help us for the movies, and we have an amazing casting director named Billy Hopkins who cast on The Butler for Lee Daniels. He’s terrific. He’s a huge fan of ours. People answer his phone call but it’s a very linear process. You submit a script to a talent. You have to give them a couple of weeks to read it. It’s not sort of a wide net. It’s a very linear process. It’s a slow process that I’m sort of not used to.

Reality shows can get up and go fast. The movie business is a very linear business. The moral of my story for anyone who’s listening is, I decided to sort of click back into what I originally set out to do 20 years ago which was to make movies. I do try to be practical and know that movies take a long time. If you read articles or blogs about independent filmmakers, sometimes you have to go back to your old gig. You know what I mean? Then, keep going.

It’s been an amazing experience so far. Again, the scary parts happen because I’m still funding the company, so I’m writing a lot of checks. You read the stories that sort of give you a stomachache then you know there’s also many stories where people have had success, and there’s been amazing, independent films. It’s a good time now because there’s so many different revenue streams for films that you’re not relied upon just sending your film to the festivals and hoping that Harvey Weinstein writes you a check.

There are other distribution channels and video on demand, and digital, and still DVD. Like I said, it’s exciting and horrifying at the same time for sure. It wasn’t a big leap because frankly many of the budgets of a single episode of some of the big giant reality shows I produced are more than the budgets of our independent movies. When I talk to investors, I’ve been responsible for budgets 12 or 10 times more than the budget of these small movies. We’ve had some success in short order with investors to hustle. You have to be fearless and not afraid to ask people for money for something that you believe in. That’s the difference.

The projects that we have, some lean more towards passion projects and one more work, one which is an action thriller definitely has piqued the interest more of our agents because it’s way more commercial and it fits much more into the formal system, if that makes sense. It’s certainly not for everybody. For me, it’s something that I would probably regret if I didn’t pursue it.

Now, are you planning on remaining the producer, and then this, it sounds like an executive producer role. Are you thinking about going into directing one of these?

Scott: The title that I’m attached to all our projects as my partner is producer. It’s funny, in the movie business, the credit hierarchy is a little different than in the TV business. The best way to explain it is the person that gets the Oscar, the Academy Award, is the producer not the executive producer. The executive producers many times, maybe someone who would’ve written a big check for your movie, maybe someone who helped you find money. It could be an executive from a small studio if it’s a studio movie or a big studio.

The role that I’m playing and my partner is playing, we’re playing the role of producers again which is slightly different semantics and reality. In reality, it’s the executive producers or the show runner who are generally in charge. Then, script to television, same thing. There’s a lot of executive producers and usually one show runner. That’s my role.

Then, we’re also running a company so we have other projects in other buckets. We have some scripts to television projects, and we have some reality projects that we’re developing as well. All the while, I haven’t sort of said to the talent, you know, I’m never going to show run a reality show again because I think that would be silly to throw away, all those years of experience. It’s something that I have jumped back into for short gigs. I do like being hyper productive and it’s nice to get a paycheck. The moviemaking process, it’s a little slower than what I’m used to. I’m sort of adjusting to it.

Right, a whole different thing. At this point, you’re looking for the money and waiting on a lot of stuff to get in place before you can start on your features. Do you feel like that’s where you ultimately want to end up then is completely just going into features then?

Scott: It would be amazing if I could do that. It’ll be amazing if I can do that. I’m practical. I mean, there’s classic stories. I think it took Lee Daniels at least five years to make The Butler. There are stories of movies that have taken 10 … I think Gravity, for some reason I recall, 10 years to the screen. It takes a long time. Since I didn’t start my path off in the film business 20 years ago, I look for shortcuts and I think the shortcuts are again being independent and trying to raise the money, and trying to attach talent, and having an amazing attorney in our team.

Yes, if one day, if all I was doing was making movies, that would be a dream come true. That’s my goal. I’m practical, and this is just practical advice for anyone who’s listening is that my day job and my former career can finance this other piece which is going to take some time. Now, the thing that can happen and this is part that’s so lovely about this business is you could get a phone call one day that could just be a game changer. You know, a phone call from an investor that you’ve been talking to and he’s willing to write you the big check instead of aggregating smaller amounts of money or you get a phone call back from a talent that means something in terms of the system. That’s the exciting part. I think you have to be a little bit of gambler.

You’re playing the long game when you do features.

Scott: You’re playing the long game. You’re also playing … You’re hoping the short game works. You’re doing everything you can. Then, just again given my background and having dedicated 20 years of my life to a very specific skill set, as much as I wake up every day and sort of put pressure on myself and put pressure on my partner that I wish things would happen faster. I can’t change the system but I can try to think of innovative ways to raise money, legal ways of course, or ways to getting to people or ways to maybe reach the producing partner of a talent as a way to get someone to read it so it’s not clogged up in an agency system that’s very busy. I have to accept the fact that those guys have a lot on their desks.

It’s funny that you say, “I think it took five years to get The Butler on the screen.” Well, I bet you that it didn’t take long once you got Oprah involved. The years are kind of the waiting game, doing all the groundwork to get that one moment with whoever it is that’s going to give you the green light.

Scott: Exactly, exactly. Then, what you hope for, and this is another reason why … and this happens I think in reality television, it happens in scripted television, and it happens in independent movies. You need one, let’s say hit, one thing to work to just to then leverage that to do the next one, and the next one. You know what I mean? That’s what we’re hoping for is let’s make … We spread our chips across the table which means we have multiple projects, let’s make one and let’s do it well. Let’s hope we can get our investors’ money back, then we can make another one.

Mike Fleiss, who brilliantly was able to leverage the success of The Bachelor into many other sales as well as anyone today on scripted television, you know, who has a hit show can leverage that into a giant eight-figure overall deal. You’re hoping for that one thing to sort of breakthrough and until you get there, it is kind of you against the world, you know what I mean, until you prove yourself. That’s some …

That’s the interesting part – is you’ve definitely proven yourself in reality, even winning Emmys but once you move into another realm, it becomes another proving game. What’s interesting in Hollywood is that you sort of are kind of never done with that. It’s whatever you most recently did. I mean, and that story’s been told a million times but it’s so true.

Scott: Absolutely. I have had the pleasure , and it’s a funny story. I’m not going to name names. I have had the pleasure of meeting with some very, very established film producers, like these are big guys who also have reality ideas and they’ll sit there, and they’ll say to me, “My movies have made hundreds of million dollars in the box office but I can’t get network approved to sell my reality show.” I get it. You’re right.

You’re known for a certain thing, right, and God bless you and I think a lot of … I’m seeing it now. I mean, I see it all the time. I get the phone calls. There’s a lot of movie companies, I mean the Weinsteins are a good example who are legitimately in the reality TV business. If you can sell shows and get revenue streams, it’s a great business. There’s companies, I think the company Asylum last week sold for $100 million. They have some hits on the air. It’s a great business. It’s true. You have to …

I mean, I haven’t gotten a lot of pushback in terms of like, “Hey, Scott. You’re out of your mind.” I just don’t come with a pedigree of a proven track record in filmmaking. I just have to convince people that I talk the same talk, really at the end of the day. For anyone who’s listening, no one gives you a handbook when you graduate from film school or your television program. You have to hustle from day one. Listen, I’m 47 and I’m still hustling. I may be hustling harder now that I ever have been.

There’s no right path but I’ve seen a lot of people do great. I’ve seen a lot of people give up, and not giving up for any bad reason. It’s just, you know, it’s a commitment and it’s supply and demand. There’s a lot of people fighting for that one job. There’s been many times where I’ve decided or I thought that I would throw in the white flag and surrender, but I haven’t. I would just scream loud, as loud as I can. If you can make it work, just figure out how to make it work.

Everyone has their own story. I’d say, tenacity and not giving up are certainly part of it. If that’s your passion, go for it. By the way, stick it out for as long as you can. Who knows? I don’t know how long I could continue to do this. It’s a grueling business. I’m not shy about saying that. It’s full of fatigue and long hours. But if you love it, I think it makes sense in the end.

It’s definitely only for those with true, true passion because that you can’t manufacture and I think people will see that if you keep at it with these stories, I think that’s what ends up getting you down the road.

Scott: Absolutely, absolutely. As passionate as I feel about making these movies, it’s as passionate as I want it to be the best PA possible and be recognized. Then, be the best associate producer possible. Just earn your place. Be the best at the video store. You know what I mean? Be the best temp assistant answering phone calls for an executive for those three days. Whatever that job is, crappy or otherwise, just do your best at it. You will get recognized. Someone will believe in your or multiple people will believe in you. Just have that tenacity to not give up.

There’s a thousand reasons that this business spits out at you every day to give up. It’s great if you can hang in there. Eventually, it’ll be a matter of time where there’s good news.

I can’t think of a better way to end our time. Thank you so much, Scott. I’m ready to see those films. Let us know when they come out.

Scott: I absolutely will. I’ll keep you posted, Ingrid. Thank you for your time.

All right. If you have questions for Scott or about producing, go to Chockalife.com.

Update!

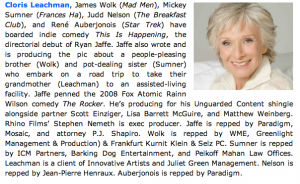

Scott’s film, This Is Happening has been completed! If you want to join the crowdfunding campaign to see this film in theaters and be a part of the magic (and get cool stuff!) go to Seed&Spark